Two years after first finding evidence of a liquid-water lake under the southern ice cap of Mars, the same research team responsible for the 2018 discovery has found evidence of even more bodies of water under the frozen Martian wastes. And even closer to Earth, evidence also surfaced for a small subterranean ocean on the strange dwarf planet Ceres.

Two years after first finding evidence of a liquid-water lake under the southern ice cap of Mars, the same research team responsible for the 2018 discovery has found evidence of even more bodies of water under the frozen Martian wastes. And even closer to Earth, evidence also surfaced for a small subterranean ocean on the strange dwarf planet Ceres.

Following up on their 2018 discovery, the Italian research team that found a 20-kilometer (12.5-mile) long, triangular-shaped salty lake buried under 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles) of Martian ice in a region called Planum Australe went back to the subsurface radar data gathered by the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft to see if there was even more evidence to help verify the lake’s existence.

The new dataset they gathered for the task was more than four times larger than the 29 radar profiles they analyzed in 2018; along with 134 new radar maps, the team also adapted radar techniques used to image hidden lakes buried under glaciers in Antarctica, Greenland, and the Canadian Arctic to make better use of the Martian radar data—techniques that helped strengthen their conclusion that the bright anomaly from a mile beneath the Red Planet’s ice was indeed a salt-water lake.

The more detailed study also revealed the presence of a number of smaller bodies of water in the surrounding area, separate from the original larger body they uncovered. The team speculates that the lakes (or ponds, in the case of the smaller reservoirs) might be composed of “hypersaline perchlorate brines”, water that contains a high concentration of perchlorate salts, a solution with a freezing point low enough that it could remain liquid in the otherwise frigid -68°C (-90.4°F) environment found deep under the Martian polar ice caps.

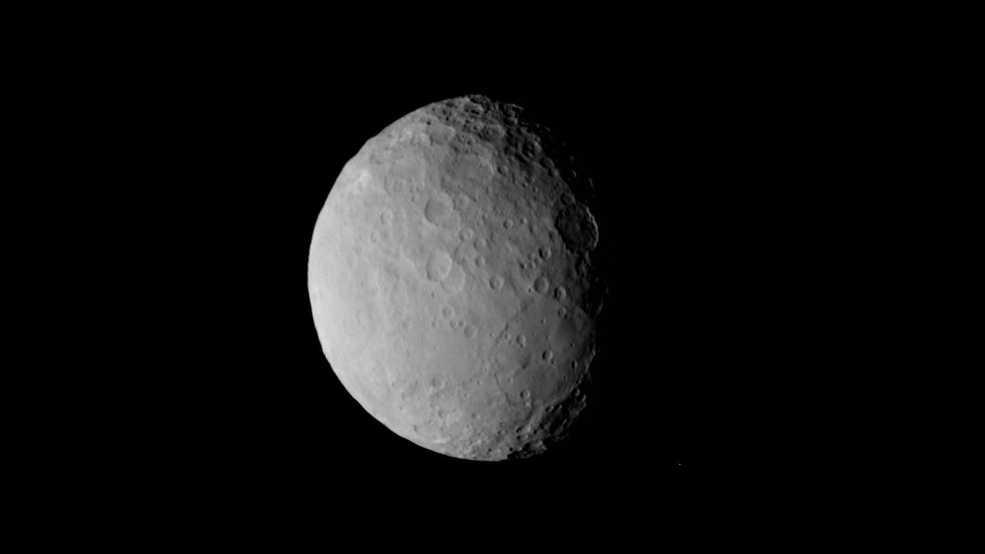

Closer to home, the dwarf planet Ceres might also have its own subsurface ocean below the enigmatic Occator Crater. Visited by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft from 2015 to 2018, the probe revealed that despite the dark color of Ceres’ surface there were bright spots present at the bottom of Occator Crater, and hypothesized that the fresh mineral deposits, along with a haze that would periodically appear above one of the spots, may be the product of the recent crystallization of salts from brines that had welled up from beneath the surface.

A recent analysis of the observations made by Dawn has uncovered evidence that Ceres may still be geologically active, with cryovolcanoes—volcanoes that erupt with ice and water, similar to those found on Enceladus—erupting from a vast subsurface ocean that has been gradually freezing over the eons.

“This elevates Ceres to ‘ocean world’ status, noting that this category does not require the ocean to be global,” according to NASA’s Carol Raymond, the agency’s principal investigator for the Dawn spacecraft. “In the case of Ceres, we know the liquid reservoir is regional scale but we cannot tell for sure that it is global. However, what matters most is that there is liquid on a large scale.”

This ocean would appear to be 40 kilometers (24.9 miles) below the surface, and may be hundreds of kilometers wide, and has impact fractures beneath the crater’s surface that allows the brine to seep up to the surface. This small ocean might have been formed by the impact that created Occator Crater 22 million years ago, and the salty brine has been slowly refreezing ever since.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

1 Comment