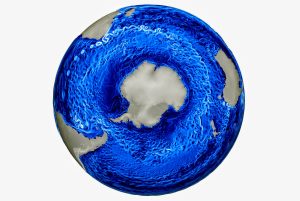

A new study is warning that fresh water from melting ice in Antarctica is slowing ocean currents in the Southern Ocean that encircles the southern continent, and is in danger of completely collapsing, much like its counterpart in the North Atlantic. The study’s models predict that the currents there will slow substantially by the middle of the century, and real-world measurements illustrate that this slowdown is already underway.

“Climate change is to blame,” explains the study’s authors in an article published in The Conversation. “As Antarctica melts, more freshwater flows into the oceans. This disrupts the sinking of cold, salty, oxygen-rich water to the bottom of the ocean. From there this water normally spreads northwards to ventilate the far reaches of the deep Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.”

While most of us are familiar with the currents that course across the surface of the ocean, such as the North Atlantic Current, there is also a network of deep-sea currents that communicate with their surface-bound counterparts that rely on a change in water temperature for the water in the current to either rise or sink to the depth where the next underwater river flows.

However, the inflow of fresh water that results from the melting of glacial ice is less dense, and thus more buoyant, than salt water, meaning that less saline currents resist the sinking of the water to the lower depths that is required to keep the whole system running. We’re seeing this phenomenon in the North Atlantic, where the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is being slowed by the influx of fresh water flowing southward from Greenland’s melting glaciers.

But now there are signs that the same problem is being experienced by the currents at the other end of the Earth: the study team constructed a high-resolution current model using temperature, wind and increased meltwater rates from glaciers. “The findings were striking,” the authors remark. “The model projects the overturning circulation around Antarctica will slow by more than 40% over the next three decades, driven almost entirely by pulses of meltwater.”

The new model also predicted a 20 percent weakening of the AMOC in the north, a factor key to the regulation of temperatures in Europe. “Both changes would dramatically reduce the renewal and overturning of the ocean interior,” the authors warn.

In addition to disrupting one of the planet’s vital heat energy distribution mechanisms, an interruption to the overturning currents would result in a corresponding disruption to the flow of oxygen and nutrients between the various layers of the ocean. “If the Antarctic overturning slows down, nutrient-rich seawater will build up on the seafloor, five kilometres below the surface,” the authors warn. “These nutrients will be lost to marine ecosystems at or near the surface, damaging fisheries.” Additionally, the lack of circulation between the surface and the ocean depths will limit how much carbon dioxide the ocean can absorb, exacerbating the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Without the inflow of warm water being circulated down into the depths, more warm water will pool around the ice at the edge of Antarctica—especially around the already-vulnerable ice shelves of West Antarctica—hastening the retreat of the ice shelves and increasing the risk that the inland glaciers that feed them will flow freely into the sea. “Put simply,” the authors continue, “a slowing or collapse of the overturning circulation would change our climate and marine environment in profound and potentially irreversible ways.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

American voters don’t care. They don’t take it seriously.

Isn’t this what the master of the key said would happen? Wow!!