Recent research into the possibility that consciousness is a quantum phenomenon has found evidence that nanoscopic structures in our bodies may be capable of sustaining quantum states necessary for such processes to occur. Previous experiments have found that molecular structures in the chlorophyll found in plant cells are capable of hosting particles in quantum states, but this new research suggests that microtubules—protein structures found in all animal, plant and fungus cells—are even better suited to this task.

The idea that consciousness is a quantum phenomenon was first presented by physicist Roger Penrose and anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff; calling their theory ‘orchestrated objective reduction’ (‘Orch OR’), they suggested that “consciousness arises from quantum vibrations in protein polymers called microtubules inside the brain’s neurons, vibrations which interfere, ‘collapse’ and resonate across scale, control neuronal firings, generate consciousness, and connect ultimately to ‘deeper order’ ripples in spacetime geometry,” according to Hameroff. “Consciousness is more like music than computation.”

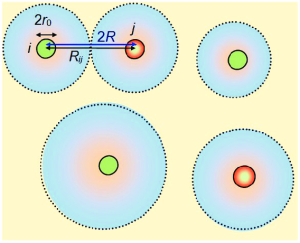

But the theory had one major criticism leveled against it: compared to the ultra-cold, precisely controlled environments required to keep individual particles in specific quantum states for use in applications like quantum computing, our brains would appear to be home to conditions that should be outright hostile to photons or electrons in entangled or superposition states.

However, in the years since Penrose and Hameroff presented their Orch OR theory, new discoveries have been made regarding how certain biological structures are not only capable of stabilizing quantum states, they may also be fundamental to basic life-giving processes such as photosynthesis.

Adding to these findings are two recent studies that found that the microtubules found in our neurons may not only be able to stabilize quantum states, they may also perform this function extremely well. While running computer simulations of microtubules to determine the structures’ capacity to maintain a coherent transfer of light energy, a research team led by Jack Tuszynski, a physicist with Canada’s University of Alberta, found that when ultraviolet light, simulated to mimic the biophotons emitted by the amino acid tryptophan, was shone through a microtubule, the light held its coherence for up to five nanoseconds. While five billionths of a second mightn’t seem very long, it is more than enough time to indicate that microtubules are capable of maintaining a coherent quantum state—thousands of times longer than what a microtubule was assumed to be capable of.

Another team with the University of Central Florida conducted a similar experiment, but instead used light from the visible portion of the spectrum. This time the light was re-emitted by the structures over much longer time periods, lasting from hundreds of milliseconds to full seconds.

“That’s the typical human response time to any sort of stimulus, visual or audio,” Tuszynski remarked while relating the UCF experiment in an interview with Popular Mechanics; he also stated that there were at least 22 independent studies that have found similar results using the tryptophan-generated UV experiment. Tuszynski went on to say that these comparatively long re-emission times are “a proxy for the stability of certain… postulated quantum states… which is kind of key to the theory that these microtubules may be having coherent quantum superpositions that may be associated with mind or consciousness.”

While these experiments don’t prove that the Orch OR theory is correct, they do offer evidence that the brain—along with virtually every other cell in the body—is at least capable of sustaining specific quantum states, re-opening the door to the possibility that consciousness may be a non-local quantum phenomenon.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

Quantum or otherwise, if the phenomenon of consciousness is ultimately dependent upon nanoscopic structures in physical bodies, then what happens when such a body (and the microtubules in its physical cells) are destroyed? Wouldn’t the consciousness dependent upon that physical body thereby simply cease to exist?

Penrose and Hameroff’s idea is that consciousness is a non-local phenomenon that isn’t generated in the brain itself, but is instead facilitated by the quantum state-sustaining capabilities of the microtubules found in our cells.

A simple analogy is that the structures act like quantum antennae that pick up on the quantum signal that is our consciousness, allowing the link between our brain and whatever we are as non-local entities.

Thanks for the clarification.

I’ve often speculated myself that, rather than being merely generated by physical brains, consciousness exists independently as a non-physical phenomenon, and requires a brain (or something physical) to act, as you say, as a sort of antenna to receive and channel consciousness so it can experience and interact with physical reality.

If so, then when the brain dies (or is damaged), consciousness is not thereby extinguished (or diminished), but simply no longer has a working receiving apparatus to interface with. (The TV is shut off, but the signal is still out there in the airwaves, broadcasting away.)

And if these antenna-like structures exist in all life forms (including plants, etc.), then brains per se are not a requirement for the reception, to whatever degree, of consciousness. This might give support to the common animistic view that everything that lives is, in some sense, “ensouled” (so to speak).

Matthew and Gwyllm: That’s how I think of it– the brain is the TV set, and the program is still being broadcast whether the TV is turned on or not.

Cell biologist Bruce Lipton has elaborated on this idea, at the level of individual cells. You might find his writing interesting.

Could this explain the coldness felt when a “ghost” is present? Hmmm

In other words, everything is an idea.