New insights into an unexplained anomaly in the Earth’s magnetic field that occurred 3,000 years ago have been brought to light through the examination of Bronze Age clay bricks inscribed with the names of Mesopotamian kings that ruled during the era. The timing of the anomaly also allowed historians to resolve a long-standing debate as to when the reigns of these kings, such as Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar II, actually occurred.

This magnetic anomaly, called the Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic Anomaly (LIAA), was a brief period that saw a dramatic increase in the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field in the region we now identify as the Middle East, with the field intensity nearly doubling for a little over 500 years. The LIAA was previously identified through the effects of the anomaly in sediment core samples taken from regions surrounding Mesopotamia—even as far away as the Azores and China—but little evidence had been uncovered directly from the region itself.

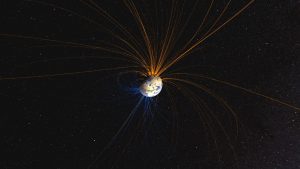

Earth’s magnetic field is constantly in flux: comprised of numerous smaller fields being generated by individual gyres that occur within the molten iron that makes up the planet’s outer core, the strength and alignment of the field can vary greatly over relatively brief periods of time, with the wandering of the north magnetic pole being a more obvious example; and also from region to region, such as the more persistent South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly, where the overall magnetic field is weakest.

Although these two examples are present-day phenomena that can be studied directly, assembling a model of what the magnetic field looked like in the past, even as geologically recent as a few thousand years ago, requires an examination of magnetic particles that were trapped in mediums such as cooled lava flows or seabed sediments while they were still aligned with the magnetic fields they were being influenced by.

But sometimes this magnetic snapshot can also be recorded in manmade objects, as illustrated by a team of international researchers that examined the magnetic signature of 32 different clay bricks that were produced in the Levant between 3,000 and 1,000 BCE. In addition to being made during the period of the LIAA, these bricks were also inscribed with the names of the twelve successive kings that ruled the region during this period, allowing the researchers to narrow down a timeline of individual fluctuations in the local magnetic field, recorded by iron oxide particles, frozen in time when the bricks were fired.

“We often depend on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia,” explained study co-author Professor Mark Altaweel, with the University College London’s Institute of Archaeology. “However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, cannot typically be easily dated because they don’t contain organic material. This work now helps create an important dating baseline that allows others to benefit from absolute dating using archaeomagnetism.”

Their analysis revealed that the anomaly was unusually strong in the region where modern-day Iraq is situated, lasting for a half-millennium between 1,050 and 500 BCE, with the field nearly doubling in strength over the millennium prior; close to the end of that period, between 604 and 562 BCE, a brief, 42-year spike in field strength also occurred during the reign of the Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar II, indicating that intense, short-term fluctuations are also possible.

While the archaeomagnetic dating process allowed the researchers to finally map field strengths in the region, the process also provided crucial context as to when the twelve kings depicted on the bricks actually ruled the region; although the order and length of their individual reigns were well documented, a starting point for this history has been the source of a long-standing debate in archeology: without continuity between Bronze Age calendars and our own modern method of timekeeping, archaeologists had to rely on radiocarbon dating to try to determine a start date for these ancient kings’ histories, a dating method that can vary on the order of centuries under certain circumstances.

The archaeomagnetic analysis of the bricks, however, was able to offer a greater resolution than radiocarbon dating, allowing the team to determine that a time period referred to as the Low Chronology was the correct timeline, placing the reign of Hammurabi between 1,728 to 1,686 BCE, and the sack of Babylon taking place in 1,531 BCE; previously, the estimates for these dates ranged between 1,848 and 1,696 BCE for the start of Hammurabi’s reign, and between 1,651 and 1,499 for when the Hittites invaded Babylon—a 152-year discrepancy for these otherwise important historical events.

In the meantime, the development of fields such as archaeomagnetism continues to unveil previously-hidden insights into the history of both our species and the planet we live on.

“The geomagnetic field is one of the most enigmatic phenomena in earth sciences,” remarked study co-author Professor Lisa Tauxe, of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “The well-dated archaeological remains of the rich Mesopotamian cultures, especially bricks inscribed with names of specific kings, provide an unprecedented opportunity to study changes in the field strength in high time resolution, tracking changes that occurred over several decades or even less.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

Thanks very much for this fascinating report.