A new study of the human genome has discovered evidence that humanity nearly went extinct nearly 900,000 years ago, due to the species having dwindled to less than 1,300 reproductively-capable individuals, quite probably from a climate-related disruption. This genetic bottleneck persisted for over 100,000 years, and would explain a gap in the fossil record from that era that is devoid of the preserved remains of our ancestors.

The researchers developed a new tool dubbed the fast infinitesimal time coalescent process (FitCoal) that they used to analyze the genomes of 3,154 present-day individuals, representing 10 African and 40 non-African populations. Their analysis found that our ancestors faced “a severe population bottleneck,” according to the study text, that occurred between 930,000 and 813,000 years ago that lasted for 117,000 years; at one point this bottleneck narrowed down to “about 1280 breeding individuals”, an event that brought our “human ancestors close to extinction.”

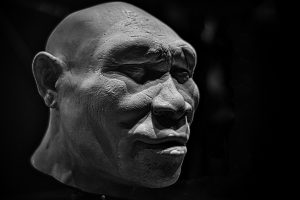

At the time that this bottleneck occurred, Homo sapiens was still a few hundred thousand years from emerging; the ancient ancestor that suffered this event is assumed to be Homo heidelbergensis, a progenitor that inhabited Africa and Europe during the Middle Pleistocene, coinciding with a major cooling event that signaled the end of one of the numerous interglacial periods that defined the Pleistocene.

“This bottleneck is congruent with a substantial chronological gap in the available African and Eurasian fossil record,” the study continues. “Our results provide new insights into our ancestry and suggest a coincident speciation event.” The authors theorize that this speciation event marked the emergence of the common ancestor that would give rise to modern humans and our Denisovans and Neanderthal brethren.

“Whatever caused the proposed bottleneck may have been limited in its effects on human populations outside the H. sapiens lineage, or its effects were short-lived,” remarked Nick Ashton, an archaeologist at the British Museum, and Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at London’s Natural History Museum. Although Ashton and Stringer were not involved in the study, they provided commentary in an accompanying article in the September issue of Science.

“This also implies that the cause of the bottleneck was unlikely to have been a major environmental event, such as severe global cooling, because this should have had a wide-ranging impact,” Ashton and Stringer explain.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

I believe I may be misreading or misunderstanding something: I thought earlier in the article the ‘bottleneck’ was attributed to a ‘climate related disruption’; ‘coinciding with a major cooling event’, while at the end it says ‘ the cause of the bottleneck was unlikely to have been a major environmental event’. Can anyone clarify?

The confusion here is because there’s two separate sources that differ on the cause behind the dieback: the authors of the study point toward an environmental event that coincided with the timing of the bottleneck, while the two experts not involved with the study offering commentary at the end point out that only h. Sapiens seems to have been affected, and not other species, implying that the cause wasn’t environmental.

Got it ~ thank you!