Northern Europe has been hit hard by a rapid succession of winter storms that have resulted in extensive flooding and storm damage across Europe, with the last two extratropical cyclones, Storms Ciara and Dennis, leaving 24 dead along paths that stretched from North America through Northern Europe. But is the slowdown of the North Atlantic Current—a consequence of global warming—the driving force that is affecting the strength of these storms?

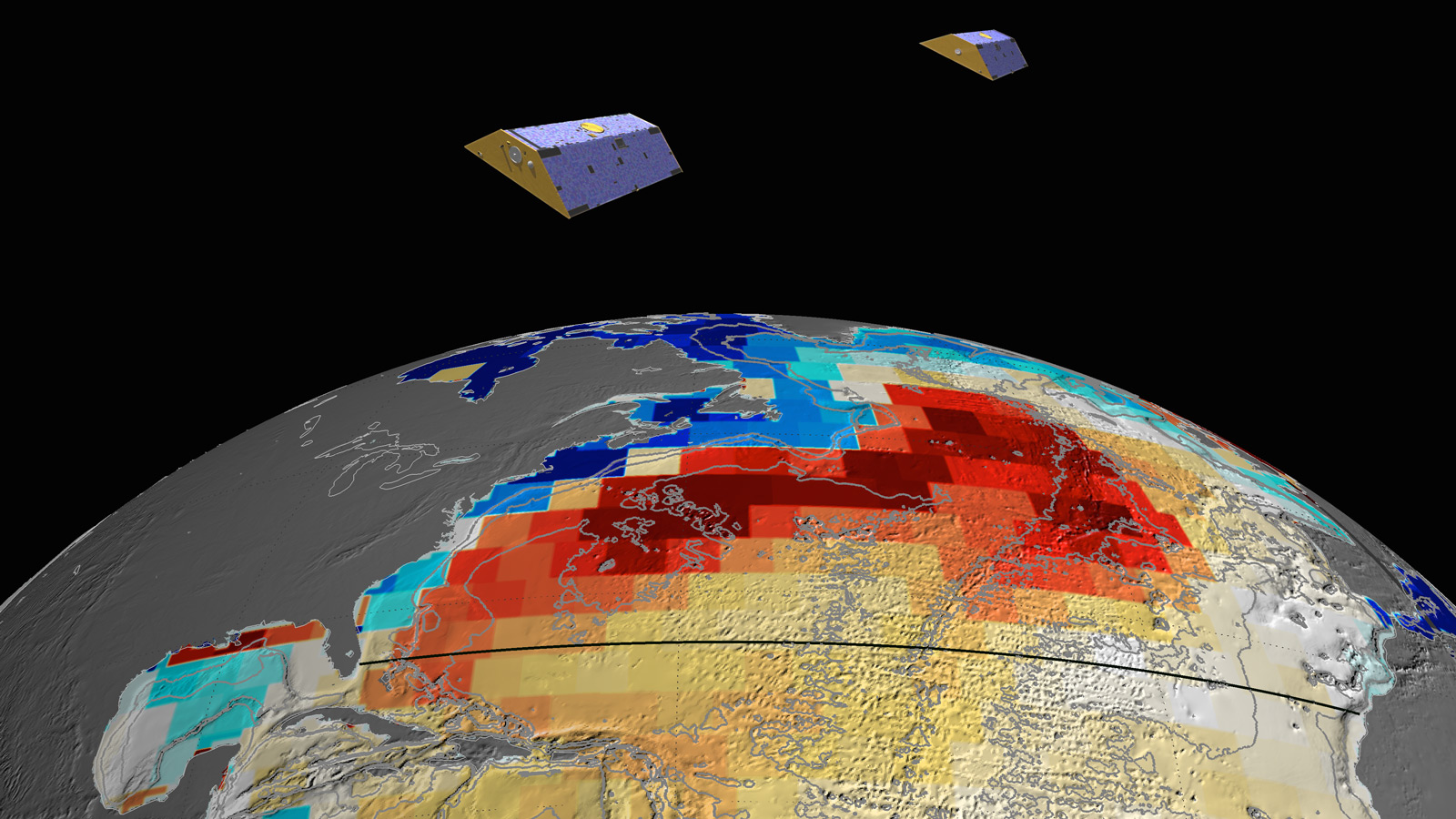

The North Atlantic Current, collectively called the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), follows a course that zig-zags northward, running from the west coast of Africa across to the Caribbean, then tracking northeast towards northern Europe. Under normal circumstances, the warm water from this southern stream cools when it meets the currents flowing south from the Arctic; this causes the water to sink into the depths where it joins another current that runs south, deep under the Atlantic, to continue its journey through the world’s oceans.

However, the accelerated melt of glaciers in Greenland has caused a large amount of fresh water to flood into the ocean where this downward convection takes place, and this fresh water, being less dense than salt water, inhibits the sinking of the currents waters, effectively producing a bottleneck that slows the entire AMOC . Recent studies have found that the AMOC has been slowing down since the 1930s, with an abrupt 15 percent decrease in current strength between Africa and the Bahamas over the past decade alone; by the end of the century, the strength of the AMOC may be cut by at least a full third.

This slowdown in the AMOC is projected to have a number of detrimental effects on weather patterns in the Northern Hemisphere, including more powerful storms across northern Europe, an effect we’re already seeing today. While Storm Ciara’s track ran along a close parallel to the stream of warm waters languishing off the US East Coast—warm Caribbean water that is being prevented from progressing northeast—Dennis’ track ran the storm directly along this run of warm water, where it experienced an explosive intensification, commonly called a weather bomb, with a central pressure drop of 84 millibars in just 54 hours, an incredibly fast rate for an extratropical cyclone. By the time Dennis reached Iceland, it had reached a near-record low pressure of 920 mb (27 inHg), and hurricane-force winds gusting up to 140 mph (230 km/h).

Although scientists still have yet to link recent storms to these projected effects, the descriptions being made match the effects being seen today. And although the scale of this season’s winter storms in Europe might be on a much smaller scale, in 1999 Art Bell and Whitley Strieber illustrated what might happen if the North Atlantic Current were to shut down entirely, resulting in The Coming Global Superstorm!

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.